Six Stunning Examples of Subterranean Structures Around the World — From Wine Cellars to Houses of Worship

From simple cave dwellings to elaborate cities, humans and their ancestors have carved out underground living spaces for millennia. Earlier this year, researchers determined that humans occupied the South African Wonderwerk Cave as early as two million years ago. More famous, perhaps, are the subterranean necropoli built by the Etruscans between 900 and 30 BCE and the cave city of Derinkuyu, which began in 700 BCE. Completed around 800 CE, Derinkuyu housed and entertained as many as 20,000 people. With floors as deep as three hundred feet below ground, Derinkuyu is one of the most impressive examples of subterranean architecture ever built. Chapels, wine cellars and other amenities were readily available to its inhabitants. In the twelve hundred or so years that followed the completion of Derinkuyu, these fully submerged structures have become increasingly rare. Our cities now rely on municipal subterranean architecture like subway tunnels but underground homes, hotels and restaurants are few and far between. Recently, architects have revisited subterranean architecture because of its ability to withstand disaster while reducing emissions related to construction and operation. From Archea Associati in Tuscany to Clayton Korte in Texas, architects across the globe are now embracing underground builds. These innovators have engineered everything from modern cave dwellings to underground art museums. Follow below to learn more about six stunning examples of subterranean coastal architecture around the world.

What is Subterranean Architecture?

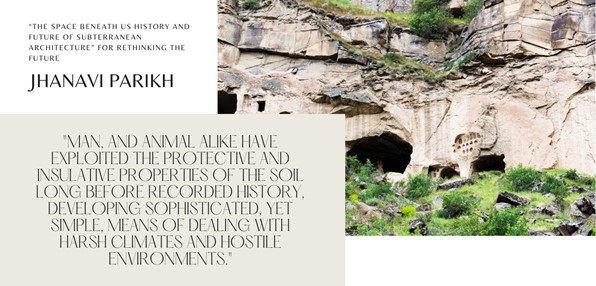

Throughout history, humans and their ancestors have crafted many different types of subterranean structures. From ancient souterrains in what is now Scotland to modern dugouts in Australia, underground structures have taken dozens of forms. Generally, subterranean architecture can be broken down into three categories: fully underground, submerged and earth-sheltered. In her article “The Space beneath Us History and Future of Subterranean Architecture” for Rethinking the Future, architect and writer Jhanavi Parikh outlines these three primary classifications of underground structures. According to Parikh, fully underground spaces are completely closed off from “the above world,” with only the entrance “above ground.” As far as three hundred feet below the surface, the city of Derinkuyu in Turkey is one example of fully underground architecture. Next, Parikh describes submerged spaces, which lie “just under the surface of the ground” and “always have direct contact with the above-ground world and natural light.”

Submerged spaces might feature “patios, atriums and domes” that limit the feeling of living underground. The dugouts of Coober Pedy in Australia are submerged buildings. Parikh identifies earth-covered buildings as the final classification of subterranean architecture. Earth-covered or earth-sheltered spaces are not technically subterranean, as they are “not entirely underground.” Rather, these structures are covered by a surface of vegetation or soil that allows them to blend into the countryside. Sometimes, earth-sheltered buildings are carved into a hillside while other times they are artificially constructed with local materials. Inhabitants of earth-sheltered buildings can walk out of these structures at ground level, rather than ascending in order to exit.

Advantages of Earth-Sheltered Structures

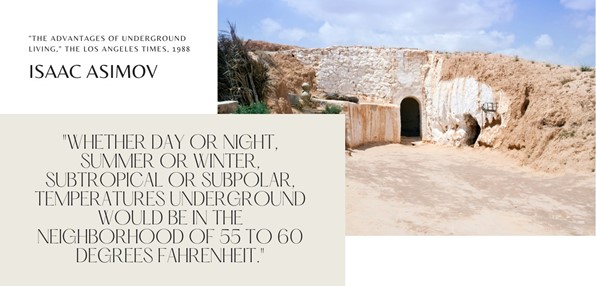

Back in 1989, biochemist and science fiction writer Isaac Asimov outlined the advantages of building underground in an article for The Los Angeles Times. The author identified energy efficiency, safety and use of sustainable building materials as three primary benefits. Rather fittingly, Asimov was an admirer of J. R. R. Tolkien — drawing inspiration from The Lord of the Rings trilogy for several of his writings. Those familiar with the English author’s high fantasy novels — and/or subsequent film adaptations — will remember the many hobbit holes carved into grassy hillsides of The Shire. In this article, Asimov waxes poetic on the many ways subterranean architecture could change the world if all humankind embraced underground living. However, Asimov also touches on existing, immediately achievable benefits of living underground. Perhaps most significantly, he notes that the internal climate of subterranean structures is relatively stable day to day and season to season all around the world.

Asimov writes that “whether day or night, summer or winter, subtropical or subpolar, temperatures underground would be in the neighborhood of 55 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit.” As such, “vast amounts of energy now expended in warming [or cooling] our surface surroundings…could be saved” and our carbon footprints massively reduced. According to the US Department of Energy, “earth-sheltered houses are even more cost-effective in climates that have significant temperature extremes and low humidity” because the soil insulates the structure from swings. Not only does the soil that surrounds subterranean structures insulate them from temperature extremes, but it also protects against natural disasters. For a similar reason, subterranean structures often require fewer building materials and rely heavily on locally sourced elements. Subterranean structures also disrupt the surrounding landscape less heinously than above-ground structures, thereby protecting wildlife and their habitats.

Challenges of Constructing Subterranean Structures

From reduced energy consumption to protection against natural disasters, there are many benefits of building underground. However, certain site-specific factors can pose a number of challenges for architects and builders. Some of the architects who designed the structures outlined below — like Archea Associati of Antinori Winery in Chianti — encountered these difficulties. Relative humidity, soil structure and quality, topography, microclimates, groundwater level and the depth to which one hopes to build all impact the viability of an underground structure.

Waterproofing the structure and maintaining healthy indoor air quality can also be challenging for builders. Depending on accessibility, quality of the site and financing options, earth-sheltered structures may initially cost more to build. Lenders may also be unwilling to finance an unconventional build. Many contributors of this higher up-front cost can be mitigated by comparably lower operating costs, however, unless the site is plagued by moisture seepage issues.

Confronting These Challenges

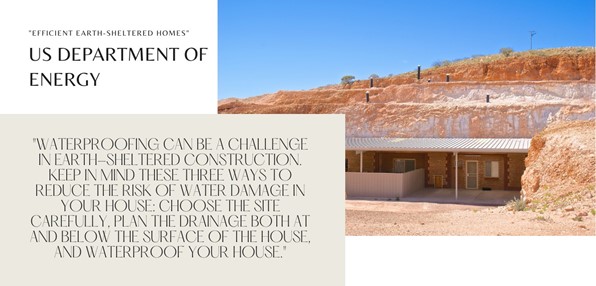

In their resource “Efficient Earth-Sheltered Homes,” the United States Department of Energy explains how to circumvent the challenges posed by underground building. According to the Department of Energy, one should opt for sites with granular soils rather than clay soils, which are impermeable and “may expand when wet.” Lots with “natural drainage away from the building” are also preferable, as this orientation prevents pressure build-up against internal and external walls.

Other issues — such as those related to indoor air quality and ventilation — can be solved by proper planning. Choosing healthy, organic furniture and building materials that have not been treated with chemicals that may off-gas is vital. Hiring the right architect should also ensure that the structure is oriented properly on the site, working with the sun rather than against it.

Six Stunning Examples of Subterranean Coastal Architecture

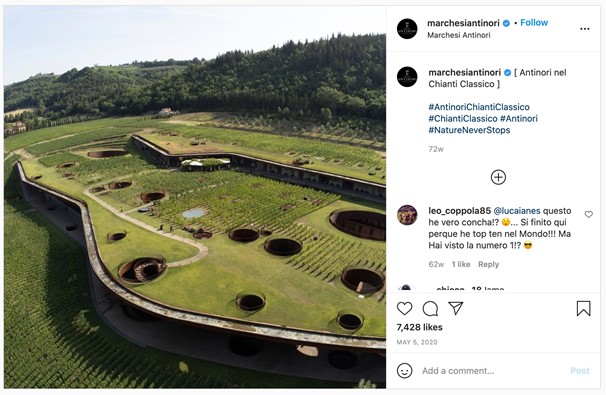

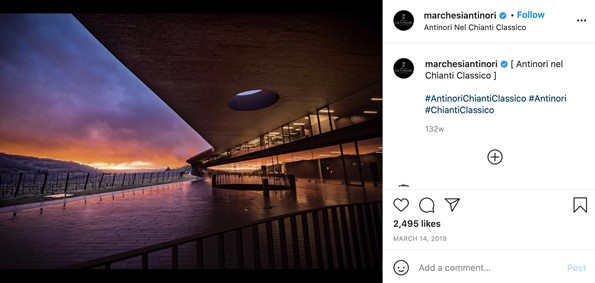

#1 Antinori Winery by Archea Associati in Tuscany

Completed in 2013 after nearly a decade of construction, Antinori Winery blends into the surrounding landscape so seamlessly that visitors easily miss it when driving in from the highway. In his article “Vines and Vintner Beautify a Tuscan Hill” for The New York Times, architecture critic Michael Kimmelman writes that “the building hides in plain sight, buried into — literally inside — a hill.” Embracing what Kimmelman calls “a vocabulary of sculptured, organic abstraction,” Archea Architects designed this structure to “become the landscape” rather than simply imitating it.

Designing Antinori Winery

A twisting driveway, sloping walls and an “undulating canopy” echo the natural curves of the hillside. Materials like Cor-Ten steel, glass, sawn-oak and tinted concrete form a powerful structure without disrupting the landscape. Terracotta walls and the natural insulation provided by the hillside keep the wine cellars temperate year round. Skylights and vaulted ceilings create a stunning interplay of light and shadow throughout the structure.

It was Marco Casamonti — founder of Archea Architects — who pushed for an unconventional structure that honored the Tuscan landscape. Casamonti was very aware of how “thoughtless development had depleted [great cultural and economic resources] in this part of Tuscany.” Because of this, Casamonti urged the owners of Antinori to consider a structure “conceived in terms of the hill.” Today — writes Kimmelman — Antinori Winery both “makes peace with its surroundings and adds a landmark to them.”

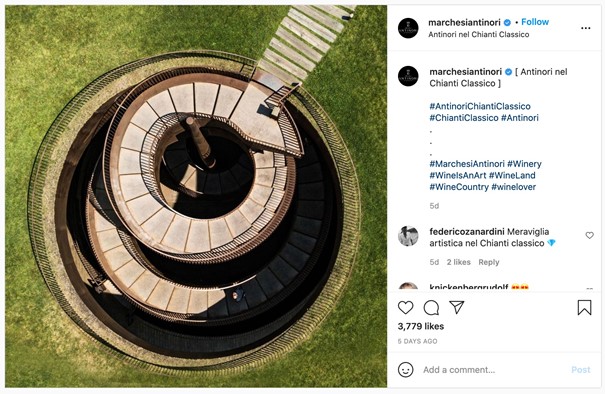

Experiencing Antinori Winery

Visitors enter the winery through a series of corkscrew staircases that “twist upward like a strip of orange peels” as shown above. Within the winery, visitors find a wine factory — where wine is processed and stored — on the lower levels. The top levels of the structure boast a visitor’s center, library, museum, gift shop, wine tasting room and auditorium.

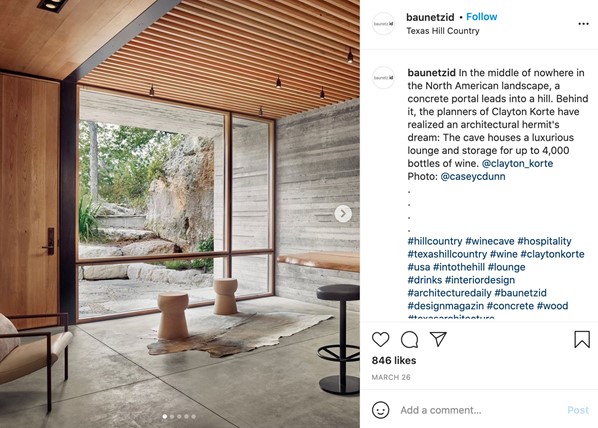

#2 Hill Country Wine Cave by Clayton Korte in Texas, USA

In 2020, American architecture firm Clayton Korte completed their earth-sheltered Hill Country Wine Cave in Texas to wide critical acclaim. Headed by Clayton Korte principal Brian Korte, FAIA, the project included designing and constructing a wine cellar, tasting room, partial kitchen and powder room — all cut into the side of a hill. In conversation with Dwell earlier this year, principal architect Brian Korte described the structure as “‘a ship in a bottle’” due to the wooden capsule that separates its interior from the bare limestone rockface. The wooden capsule not only protects the structure from loose earth in the cave but also from moisture. Sprayed concrete interior walls replicate the texture and tones of natural limestone without risks posed by direct contact with the hillside.

Designed with sustainability in mind, Dwell writer Kathryn M notes that Korte and his team sourced local building materials for the project. Primary building materials — including white oak, Douglas fir, reclaimed cedar, steel and concrete — were sourced from vendors within 500 miles of the site. Surrounding this subterranean structure is a forest of elm trees and oak trees. Over the next few years, Clayton Korte hopes indigenous foliage — such as ivy and moss — will shroud the entrance even further, seamlessly integrating it with the hillside. Describing the project to Dwell, Korte notes that embedding the wine cave into the hillside “‘contributes value to the larger environment by appearing as a stealth destination that calls little attention to itself.’”

Design Team and Critical Response

Texas-based firm architectural firm Clayton Korte worked with SSG Structural Engineers, Positive Energy, Studio Lumina, Intelligent Engineering and Monday Builders on the Hill Country Wine Cave. Many of the vendors and consultants with which Clayton Korte collaborated — including Studio Lumina, Intelligent Engineering and Monday Builders and Positive Energy — are local to Southwestern Texas.

Since its completion last year, the Hill Country Wine Cave has both received and been nominated for countless top design honors. The Hill Country Wine Cave as recently recognized as an Honor Award winner in the 2021 Residential Design Architecture Award and as a Merit Award winner by AIA San Antonio. Clayton Korte’s subterranean build is also the winner of the 2021 Architizer A+ Award for Bars & Wineries and the 2021 Regional Luxe RED Awards for Wow-Factor Room — among many others.

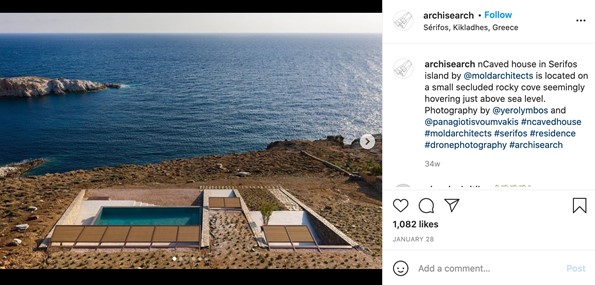

#3 NCaved House by Mold Architects on Serifos Island

Designed by award-winning Greek architectural firm MOLD Architects in 2020, NCaved hovers above the sea on the Mediterannean island of Serifos. The pyramidal three-level residence features a master suite (top floor), living space (middle floor) and guest house with a pool (bottom floor) arranged in a grid — all with spectacular ocean views. A series of internal and external staircases connect the three levels. MOLD describes the internal staircase as one of the most special elements of their design, noting that it slowly unveils “initially hidden spaces of the house, while framing a two sided view: a visual outlet to the sea during the descent, an outlet to the sky during the ascent.”

‘Rough and Natural’ Materials Hide NCaved in the Cliffside

MOLD Architects’ NCaved house capitalizes on each of the benefits outlined above that commonly apply to subterranean structures. The cliffside protects NCaved from blustery northern winds and sea spray while insulating it from changes in temperature and reducing energy consumption. Unlike other homes on the island, NCaved meshes perfectly with the surrounding landscape. In her article “NCaved, An Arresting Holiday House By MOLD Architects Blends Into The Edge Of A Cliff” for IGNANT, by Stephanie Wade notes that the firm “aimed to create a ‘rough and natural’ aesthetic in the home, and so decided to extract rocks from the site and repurpose them as walls.”

The firm opted for materials like “stone, exposed concrete wood and metal” to create a hideaway “where raw materials paired with a stripped-back and minimalist interior mimic the natural beauty of the island.” Reflective surfaces and neutral tones chosen by MOLD direct attention towards the ocean while making the home feel as though it is floating in mid air. Floating stairs, slatted walls made from raw wooden planks, stone walls, sleek monochromatic built-in furniture and sunken living spaces add to the ethereal atmosphere of this home. The firm partnered with Studio 265, Team M-H, Nikos Andrianopolous and qoop to create a bioclimatic home that is well-insulated, properly ventilated and incredibly energy-efficient.

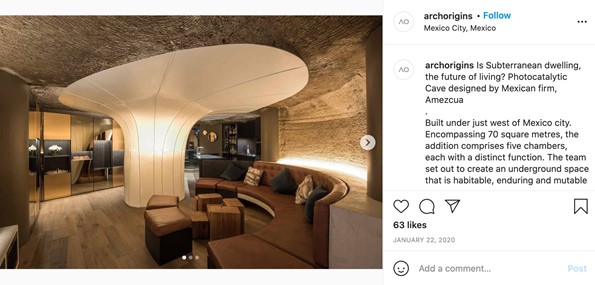

#4 Photocatalytic Cave by Amezcua in Mexico City, Mexico

Local design firm Amezcua designed Photocatalytic Cave as an addition to their client’s 20th century home, which is located just outside Mexico City. Depending on the day, the Cave functions as either a party pad or a quiet retreat for the owners and their guests. Nestled beneath a residence originally designed by postmodern architect Manual Rocha Diaz and sculptor Ernesto Paulsen, this subterranean structure replicates Diaz’s design sensibility while taking inspiration from ancient cave dwellings.

Amezcua transformed an existing salt mine — commonly found in this part of Mexico — into their Photocatalytic Cave using oak, limestone, concrete, Krion and glass. The home’s subterranean addition includes a kitchen, living room, media room, wine cellar, smoking lounge, dining room and powder room.

Ancient and Innovative Materials Combine in Mexico City’s Photocatalytic Cave

Though the entire addition is awe-inspiring, sculptural elements made from photocatalytic composite material Krion are some of its most innovative and intriguing. According to Jenna McKnight in an article for Dezeen, Krion was chosen for this underground space because it “can help diffuse light and purify the air.” As mentioned above, properly lighting and ventilating underground spaces can be difficult. Krion panels wrap around both the organic partition that separates the living room and kitchen and around the light installation designed by artist Emilio Garcia Plascencia. Many of the home’s furnishings were crafted on-site, with Rodolfo Díaz Cervantes creating a vanity made of marbled concrete that reflects the striations of the limestone behind it.

Cervantes’ vanity underscores one of the project’s primary goals, notes Jenna McKnight in an article for Dezeen. This goal was to “reveal the cave’s evolution over time.” Quoting the team of architects at Amezcua who designed Photocatalytic Cave, McKnight writes that the structure’s “‘beauty is in its nature and the reading of time observed in the strata of its walls.’”

Design Team Behind Amezcua’s Photocatalytic Cave

Designers Gabriela Mosqueda, Aarón Rivera, Rodrigo Lugo, Miguel González, Saraí Cházaro, Víctor Cruz, María García, Mauricio Miranda and Julio Amezcua collaborated on the project. MM Desarrollos, Porcelanosa, Gabriela Diaz, Luz en Arquitectura, Light Moxion, Taller Tornel, JM Construcciones, Forte/Solesdi and Stylus Audio & Video also contributed to the build. Porcelanosa — which engineered the Krion K-Life solid surface interior lining for Amezcua’s Photocatalytic Cave — has worked on several other subterranean structures. One of the most notable is Aquatio Cave Luxury Hotel & Spa within Italy’s Matera Sassi UNESCO World Heritage site.

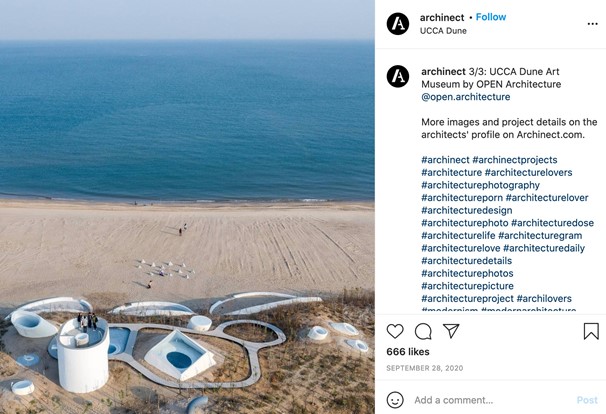

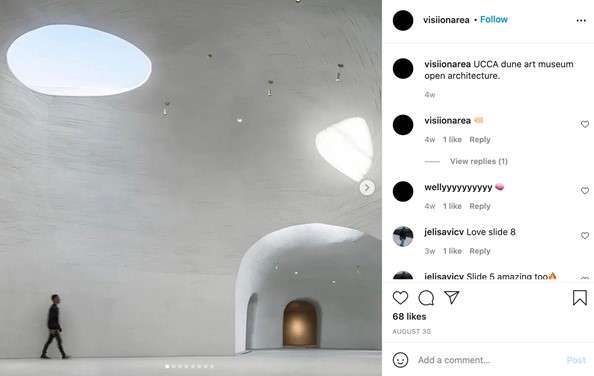

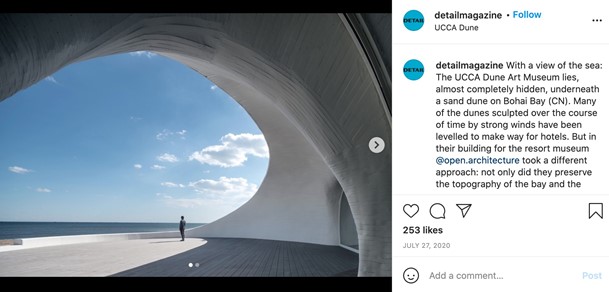

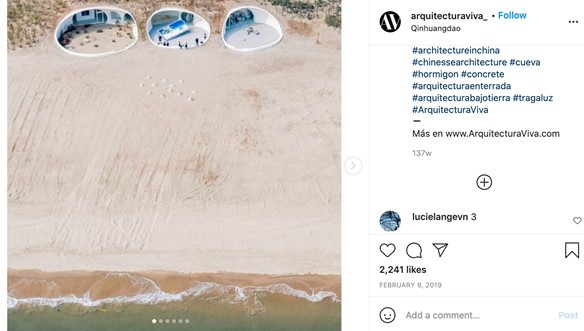

#5 UCCA Dune Art Museum by Open Architecture in Qinhuangdao, China

The UCAA Dune Art Museum was designed by Beijing-based architecture studio Open Architecture and constructed over the course of three years along the coast of northern China. Mostly submerged with portals that allow light and visitors to enter the ten galleries, the museum was designed to replicate the sand dunes that surround it. Both the museum itself and most of the furniture within the building were thoughtfully designed by Open Architecture co-founder Li Hu and hand-molded on site by a team of local builders. According to Open Architecture, Li Hu and his team “deliberately retained the irregular and imperfect texture left by the formwork, allowing traces of the building’s manual construction to be felt and seen.” When asked about the underground museum by Dezeen’s Katie de Klee for her article “Open Architecture builds cave-like art gallery inside a sand dune,” Li Hu noted that “‘the walls of ancient caves [are] where art was first practiced.’”

Sustainability of Open Architecture’s Subterranean Museum

Li Hu and his team hope that the Dune Art Museum will function as “‘a place to thoughtfully contemplate both nature and art’” and as a nature preserve. Quoted by Kathryn M in her article “This Otherworldly Museum in China Is Buried Beneath the Earth” for Dwell, Li Hu explains the latter intention. Li Hu explains that because of the Dune Art Museum, the dunes and the delicate coastal ecosystems that surround them “‘will be preserved instead of leveled to make space for ocean-view real estate developments.’” Sadly, notes Li Hu, this thoughtless destruction “‘has happened to many other dunes along the shore.’”

Clearly, Open Architecture designed the Dune Art Museum with sustainability in mind. In addition to protecting its natural surroundings, Open Architecture ensured that the museum has a minimal carbon footprint. A series of skylights naturally illuminate the galleries while a low-energy ground source heat pump prevents the need for air conditioning during the heat of summer. A roof covered with sand also protects the galleries from heating up.

Open Architecture Designs the Sea Art Museum as a Companion to the Dune Art Museum

Beijing-based firm Open Architecture has designed a number of other art institutions and cultural centers across China — many of which prioritize the relationship between visitors and nature. These include the New Shenzhen Art Museum and Library, the Pudong Art Museum and the Gehua Youth and Cultural Center. Upon completion of the UCAA Dune Art Museum, Open Architecture designed a complementary gallery called the Sea Art Museum.

Unlike the Dune Art Museum, the Sea Art Museum will “rise out of the sea like a solitary rock.” While the Dune Art Museum offers visitors a total of ten galleries, a cafe, a reading room and a look-out, the Sea Art Museum will have only a single gallery, behind which select artists are invited to work in a hidden studio. This single gallery will exhibit just one piece of art at a time. In 2019, a pier was built that will connect the two galleries, though the Sea Art Museum will only be accessible by the causeway during low tide.

#6 Temppeliaukio Church by Timo and Tuomo Suomalainen in Helsinki, Finland

Also called the “Church of the Rock,” Temppeliaukio Church was designed by architects Timo and Tuomo Suomalainen in Helsinki, Finland during the 1960s. Timo and Tuohomo Suomalainen designed this church for the Lutheran parish of Töölö after winning a contest held by the Finnish government. While the government planned to erect a house of worship for the seaside Töölö community as early as 1906, wartime spending — and later reparations — during the World Wars prevented the project from moving forward.

By 1961, Finland had finished paying reparations related to the Second World War and was able to fund the new Töölö community church. Though designs submitted by the Suomalainen brothers were experimental, the Finnish government not only accepted but embraced it. In her article “A Brief History of Helsinki’s Temppeliaukion Church” for Culture Trip, Jennifer Wood explains. According to Wood, the Finnish government approved the Suomalainens’ plans because the granite drum of the building would result in “excellent natural acoustics” for the church.

Designing Temppeliaukio Church

Despite some resistance from the public, by 1969 the circular Lutheran church and event venue was complete. A construction crew successfully carved the church directly into the granite rock face of Töölö, forming ducts around the base of the church to allow snow and rain to flow around the building. A copper dome hovers over the church, set atop slatted stilts that allow light to filter into the building.

Between these slats are a series of one hundred and eighty windows of varying heights and widths. According to Wood, this flood of light is especially magical in the early morning, when it illuminates the altar, which was “made from an ice-age crevice.” Unlike other subterranean structures in this list, the granite walls of Temppeliaukio Church remain uncovered and completely natural. Temppeliaukio Church remains popular today, attracting visitors from across the globe.